Ben Jacques

Post-election analysis has included a lot of finger-pointing about why Kamala Harris lost. Yet the simple truth is that Donald Trump won because white people, the demographic majority, voted for him. About 60 percent of whites went for Trump. And a huge portion of these came from Christians. People like me.

“White Christians made Donald Trump president—again,” headlined the Religion News Service.

“Trump’s Path to Victory Still Runs through the Church,” proclaimed Christianity Today.

CNN exit polls revealed that 72 percent of white Protestants and 61 percent of white Catholics voted for Trump. Among white Christians who identified as evangelical or “born again,” the percentage was 81.

Among Christians of all races, Trump still won a clear majority: 63 percent of Protestants and 53 of Catholics. A significant boost in the Catholic vote, especially in swing states, helped put Trump over the top. “Jesus is their savior, Trump is their candidate,” ran an Associated Press headline.

But not all Christians voted for Trump, and a sizable minority has reacted with shock that someone known for racist and misogynistic behavior, vulgar language and threats of violence could win the support of those claiming to be followers of Jesus?

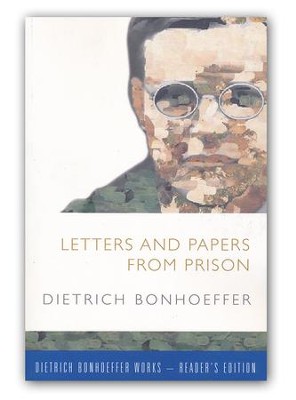

An answer may be found in the release in theaters this month of the movie, “Bonhoeffer.” The film is based on the life of the German pastor and theologian, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, executed by the Nazis in 1945. While the film highlights the dissident’s role in a plot to assassinate Adolf Hitler, the real lessons for us can be found in the years leading up to World War II.

By 1933, when Hitler was elected chancellor, Germans were well aware of his hatred of Jews. As early as 1920 he had labeled them an “alien race” and called for their “irrevocable removal.” Once in control, Hitler began the progressive persecution of Jews and other undesirables. Soon after his inauguration, he released the Aryan Paragraph, barring Jews from civil service and multiple professions. In 1935 the Nuremburg Laws stripped them of citizenship.

In November of 1938 state-sanctioned mobs brutally attacked Jews throughout Germany and its territories, destroying businesses, homes and synagogues. Ten thousand Jewish men were arrested and sent to concentration camps. By the time World War II started, the “final solution” of six million Jews throughout Europe was well underway.

From the German population, 95 percent Christian, the Nazis drew wide support, playing on anti-Semitic and nationalistic themes, heightened by propaganda and misinformation. Following Hitler’s election, one church leader wrote: ‘A fresh, enlivening and renewing reformation spirit is blowing through our German lands….The word of God and Christianity shall be restored to a place of honor.”

In 1933 Hitler appointed Ludwig Müller, an openly anti-Semitic Lutheran cleric, as Reichbishof. In this role, he was to proclaim “positive Christianity.” Mueller presided over the consolidation of the Evangelical (Lutheran) Churches of Germany, representing a majority of German Christians.

In a revision of history, the bishop claimed that Jesus was not a Jew, but an Aryan. In a statement clarifying church policy, he wrote that Jews posed a threat by bringing “foreign blood into our nation.”

One of the Mueller’s early acts was to demand that churches fire any pastors of Jewish ancestry or those married to a Jew. He also ordered all pastors to sign a loyalty oath to the Führer.

Not everyone, however, submitted to the nazification of the German Church. Dietrich Bonhoeffer and other dissidents, refused to submit to church control. In 1933 they formed the Confessing Church.

Throughout Bonhoeffer’s years as pastor, teacher, author and seminary director, he struggled to find his role in the Third Reich. While his early protests centered on preserving church autonomy, he increasingly spoke out against the Reich’s treatment of Jews. He wrote: “Only the person who cries out for the Jews may sing Gregorian chants.”

In time Bonhoeffer understood his mission as going beyond protest to political action. In 1939 he returned from the United States, where a position had been created at Union Theological Seminary expressly for his safety. Back in Germany, he joined the Abwehr, the German Intelligence agency. He was hired by his brother-in-law, Hans von Dohnanyi, on the pretense that the cleric’s many ecumenical contacts would make him an asset. Unknown to the Nazis was his brother-in-law’s role in the Resistance.

In 1943, after the Gestapo found incriminating papers, Bonhoeffer was arrested and imprisoned. On April 9, 1945, just days before American troops liberated the prison camp, he was hanged.

Bonhoeffer was not the only Christian leader to stand against Hitler. The number, however, was small. Most church leaders, including those of smaller denominations, found it expedient to accommodate Nazi ideology. Years later, Harold Alomia, a Protestant pastor and historian, would write: “God’s bride danced with the Devil.”

As we begin life under a second Trump presidency, enabled largely by the votes of white Christians, Bonhoeffer’s story is a warning of what can happen when race hatred and Christian nationalism are joined. American voters, Christian voters, please pay attention.