Is it you then that thought yourself less?

The question, posed long ago by Walt Whitman, is still fresh in my mind. It’s a line from “Song for Occupations,” Whitman’s ode to the working class, published in 1855. In intimate conversation with the reader, the poet is clarifying what is of most value in our lives.

The question resonates today as then. Who among us has not, in a society that values wealth and achievement above all else, felt themself to be less?

I remember asking that question of my students years ago as we sat around a long table at a Massachusetts public college, reading aloud Whitman’s poems. The course was New World Voices, and the bard from Long Island was the foundation.

Whitman was a contemporary of Ralph Waldo Emerson, Emily Dickinson, and Edgar Allan Poe, yet his poems are nothing like theirs. He exploded all poetic norms to fashion a new American verse, free verse. He loved the vernacular and the natural rhythms of speech. The pal of workers and prostitutes, fugitives and suffragists, he called for democracy to extend into all aspects of human life, including the home.

When I taught Whitman, we’d begin with “When I Heard the Learned Astronomer.” In this poem, the narrator listens to a lecture on astronomy, but tiring of this, walks out to an open field to gaze directly at the stars.

Next, we would read “Song of Myself,” Whitman’s 52-stanza celebration of being alive, the heart of “Leaves of Grass.” But it was when we came to “Song for Occupations” that I sensed my students most identified with the poet’s words.

In this six-part poem, Whitman catalogs working people in cities and farms — plowers, milkers, millers, ironworkers, glassblowers, sailmakers, cooks, bakers, carpenters, masons, surgeons, and seamstresses.

The poem, published in 1855, is vibrant in detail, cataloging both laborers and their tools.

The pump, the piledriver, the great derrick . . the coalkiln and brickkiln, Ironworks or whiteleadworks . . the sugarhouse . . steam-saws, and the great mills and factories;

The cottonbale . . the stevedore’s hook . . the saw and buck of the sawyer . . the screen of the coalscreener . . the mould of the moulder . . the workingknife of the butcher;

The cylinder press . . the handpress . . the frisket and tympan . . the compositor’s stick and rule

“Why should we care?” I remember asking my students — themselves the sons and daughters of carpenters and electricians, nurses and social workers, teachers and technicians.

After a pause, one young woman answered: “Because it all matters. Our lives and the work we do matters.”

She had, of course, identified the central theme of Whitman’s art: the immeasurable value of each human being, regardless of class, gender, race, religion, or occupation. Aware of society’s prejudices, Whitman returns to this theme again and again.

Is it you then that thought yourself less?

Is it you that thought the President greater than you? Or the rich better off than you? Or the educated wiser than you?

If so, he has an answer:

I bring what you much need, yet always have, / Bring not money or amours or dress or eating . . . . but I bring as good.

It eludes discussion and print, / It is not to be put in a book . . . it is not in this book.

In the cadences of a preacher he continues:

You may read in many languages and read nothing about it; / You may read the President’s message and read nothing about it there: / Nothing in the reports from the state department or treasury department . . . . or in the daily papers or the weekly papers, / Or in the census returns or assessor’s returns or prices current or any accounts of stock.

Today, as then, I can still hear Whitman whisper:

The sum of all known value and respect I add up in you whoever you are; / The President is up there in the White House for you . . . . it is not you who are here for him.

What Whitman offers in this poem is the gift of ourselves and those around us, an acceptance enriched by his democratic vista. In line after line he reminds us that we are, ourselves, the goal of science, art, laws, politics, commerce — and, yes, education.

It’s a good lesson for all, because it affirms what is of most value in a society prone to power mongering and elitism. And it’s a tender reminder that happiness is not tied to wealth, but to other human beings.

Whitman closes “A Song for Occupations” with an elegant affirmation. Praising the singer over the psalm, the preacher over the sermon, the carpenter over the pulpit he carved, he exclaims:

When a university course convinces like a slumbering woman and child convince,

When the minted gold in the vault smiles like the nightwatchman’s daughter . . . I intend to reach them my hand and make as much of them as I do of men and women.

Walt Whitman’s voice is good medicine for us today. Wherever we are, in a classroom or on the subway, he calls us to our shared humanity. Open your eyes, he is saying, to those around you, whether engineer or washer woman. And keep a lookout for the smile of the night watchman’s daughter.

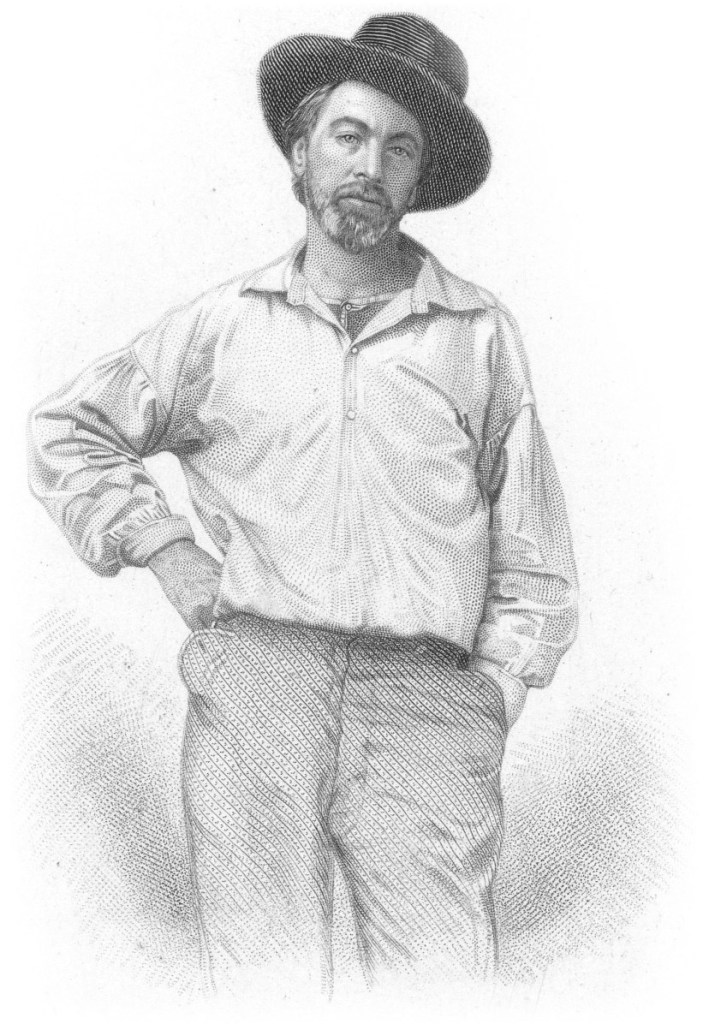

Art: Walt Whitman. Steel engraving by Samuel Hollyer from a lost daguerreotype by Gabriel Harrison. Used as frontispiece in 1855 (1st) edition of Leaves of Grass. Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division: //hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/cph.3b29437

Note: This essay was published by the Boston Globe on August 3, 2025.