A fugitive, he got off the boat in Newport and continued by coach to New Bedford. There, in the whaling seaport founded by Quakers, he found safety. He also found work.

“There was no work too hard—none too dirty,” he would write. “I was ready to saw wood, shovel coal, carry wood, sweep the chimney, or roll oil casks.”

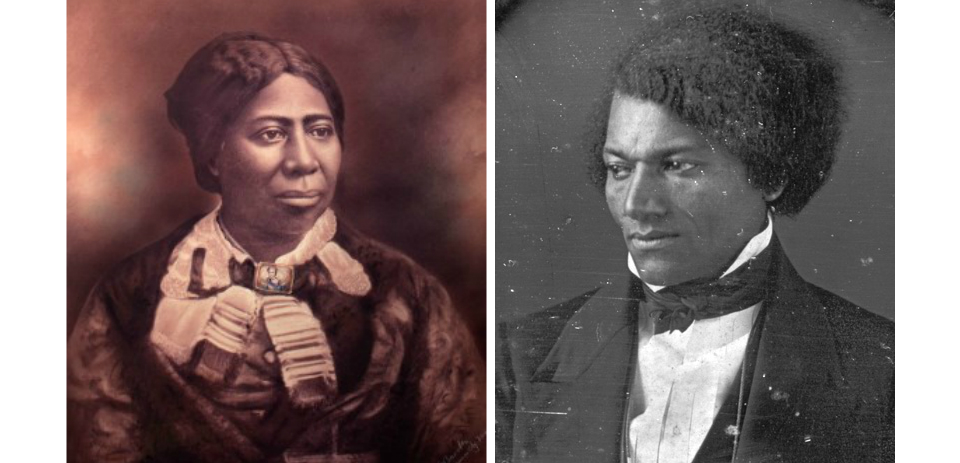

His name was Frederick Douglass and for first time in his life, he was working for himself and his newly married wife, Anna. “It was the first work,” he wrote, “the reward of which was to be entirely my own. There was no Master Hugh standing ready, the moment I earned the money, to rob me of it.”

The year was 1838. Dressed as a sailor and using false papers, the young man (he was just 20) had fled Baltimore. Having found a haven in New Bedford, he was amazed at its wealth and absence of poverty. “I had somehow imbibed the opinion that, in the absence of slaves, there could be no wealth, and very little refinement.”

He continued: “Everything looked clean, new, and beautiful. I saw few or no dilapidated houses, with poverty-stricken inmates; no half-naked children and barefooted women, such as I had been accustomed to see.”

Instead, Douglass found a city bustling with commerce and men and women eagerly engaged in their work. “I saw no whipping of men; but all seemed to go smoothly on. Every man appeared to understand his work, and went at it with a sober, yet cheerful earnestness….”

Most surprising was the condition of fellow fugitives and free Blacks. “I found many, who had not been seven years out of their chains, living in finer houses, and evidently enjoying more of the comforts of life, than the average of slaveholders in Maryland.”

His friends, Nathan and Polly Johnson, who had taken him and Anna into their home, “lived in a neater house; dined at a better table; took, paid for, and read, more newspapers; better understood the moral, religious, and political character of the nation,—than nine tenths of the slaveholders in Talbot county Maryland. Yet Mr. Johnson was a working man. His hands were hardened by toil, and not his alone, but those also of Mrs. Johnson.”

Even though New Bedford had become a refuge for escaped slaves, there was still racial prejudice. In Baltimore, Douglass had worked as a ship’s caulker, but was refused work with the white caulkers here, work which would have earned him twice his laborer’s wage.

Still, he and his wife made a living and found their own apartment. They attended church and socialized with others in the community. As a boy he had been taught to read by the sympathetic wife of his owner. Now he scoured the pages of The Liberator, published in Boston by William Lloyd Garrison.

Three years later, at an abolitionist meeting on Nantucket, he was asked to tell his own story, and the rest is history. He went on to become perhaps the most eloquent champion of the anti-slavery cause, lecturing, editing, writing and speaking throughout the Northern States, England and Ireland. A friend of all those yearning for freedom, he was an advocate for women’s rights as well.

Remembering Frederick Douglass is fitting as we celebrate Black History Month. But it’s also important given the threats to the human rights of millions of those in our nation today threatened with deportation. Like him, they have sought refuge among us. Like him, they will work at anything to provide for their families. Like him, they have stories to tell.

As the Trump administration carries out raids, as it dehumanizes men, women and children because of their immigration status or gender identity, I can’t help wondering what Frederick Douglass what would have to say.