Our President is attacking the Smithsonian for its portrayal of slavery. He wants exhibits that show the horrors of slavery taken down. We don’t want our children to get the wrong idea.

It reminds me of comments I heard in the ‘60s. Comments like, most slave owners treated their slaves like family. Or, slaves benefited from slavery because they could learn a trade—a viewpoint recently written into the Florida public schools curriculum.

Which brings me to a document that surfaced this summer in the Stoneham Public Library titled “A History of the Black in Stoneham.” Written in 1969, it was published in the Stoneham Independent.

Disregarding the awkward reference to “the Black,” the reader is left with the impression that slavery was not so bad.

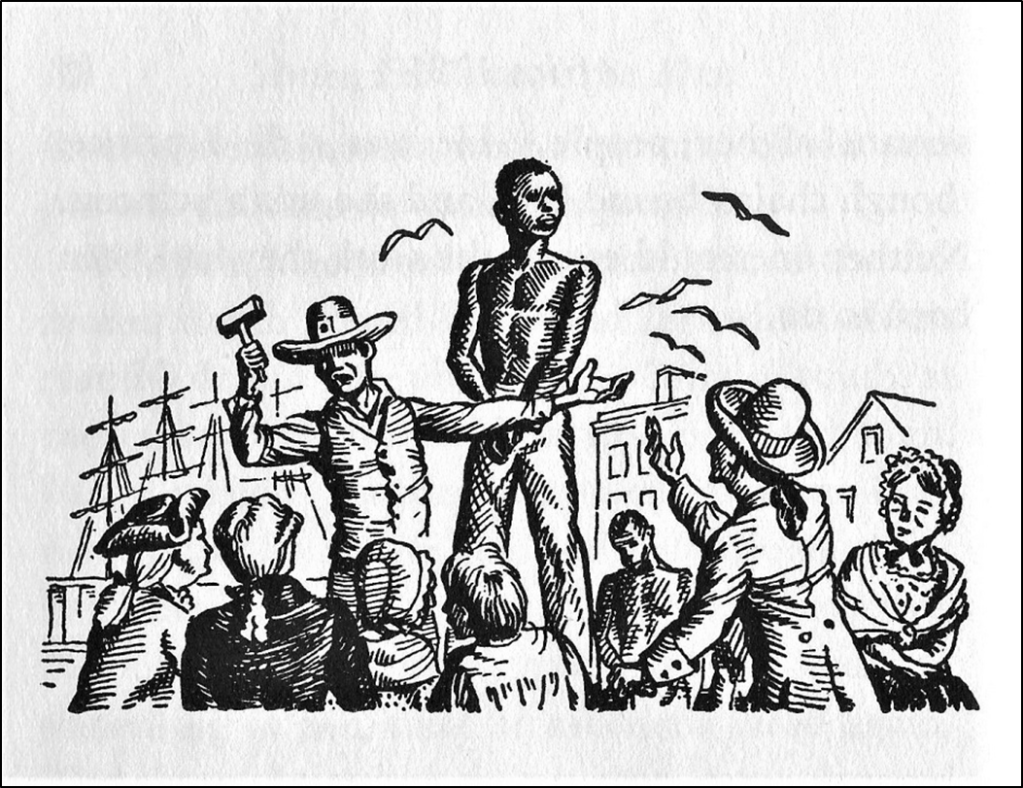

The article covers three periods, Colonial, pre-Civil War, and modern, and provides much good information. But it starts to break down when it compares slavery to indentured servitude, implying little difference. The authors failed to distinguish between the contractual—and finite–obligations of the indentured person and the ownership in perpetuity of slaves and their offspring. In other words, barring exceptional actions by their owners, enslaved men, women and children labored with no rights and no expectation of freedom. They were chattel.

That hopelessness is expressed in the will of one slave owner: “I bequeath unto my son … one negro woman named Fanny and her children now in his possession and one Negro man named Harry and all their increase to him and his heirs forever.”

A few of the article’s statements about enslaved people in Stoneham can only be described as absurd, like this one: “They were all shoemakers and they laid stone walls, but none was exploited!” And another: “Conditions must have been good because free blacks settled here.”

As we celebrate three hundred years of our history, it’s important to understand the role slavery played in Stoneham. It’s important to know that apart from how individuals were treated and the degree of physical trauma or deprivation they endured, they would have suffered deep and lasting psychological wounds.

Some basic facts. From the colonial period, we have records of some three dozen enslaved men, women and children in Stoneham. Named and unnamed, they show up in church and town records, wills and inventories. Like a “Negro woman and her children” mentioned in Daniel Green’s will. Like the 8-year-old “Mulatto Negro” purchased by James Hay in 1744.

Like “a Negro named Cato, the son of Simon, a Negro servant of Deacon Green,” or a maid named Dinah, owned by the school teacher William Toler.

Like a woman named Phebe, purchased that same year for 75 British pounds by the Rev. James Osgood, and listed along with his house furnishings after his death as simply, “a Negro Woman—70 £.”

Like Jack Thare, 40, “a servant of Joseph Bryant, Jr.,” one of six free or enslaved Black men from Stoneham who fought at Bunker Hill. When Jack failed to return from his enlistment, his master posted a fugitive want ad. Here’s what it said:

Ran away from the subscriber on the 24th of February, a Negro fellow, named Jack, of a — stature, has lost his upper teeth; had on when he went away, a blue coat, with large white buttons. Whoever will take up said Negro, and convey him to the subscriber in Stoneham, shall have three dollars reward. Joseph Bryant, Jr.

The 1969 article on Blacks in Stoneham was published the year I graduated from college. Our nation was still reeling from the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. We were being challenged to examine not only our actions and prejudices, but a long history of subjugation and dehumanization of Black people.

As we celebrate our Tricentennial, let’s look honestly at our history. The value of doing so is that it will affect who we will become. By insisting that we tell the truth about our past, we commit to embracing the full humanity of all those around us.