It happened on Patriots’ Day, April 19, 1861

By Ben Jacques

When President Abraham Lincoln on April 15, 1861, called for a voluntary army to protect the nation’s capital, the first to arrive in Washington were the Massachusetts Sixth Voluntary Infantry. Although the men came from all walks of life, most were mill workers and farmers.

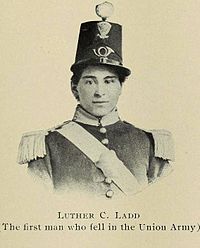

One of them, Luther Crawford Ladd, was a 17-year-old worker in the Lowell Machine Shop. Another from Lowell, Addison Otis Whitney, 22, worked in the Number Three Spinning Room of the Middlesex Corporation.

Down river in Lawrence, Sumner Henry Needham, a 33-year-old lather, was also quick to enlist. Others came from Acton, Groton, Worcester, Boston and Stoneham. Of the 67 volunteers from Stoneham, 51 were shoemakers. One of them, 19-year-old Victor Lorendo, played in the regimental band.

Summoned to Boston by Governor John Andrews, the Sixth was a regiment of “patriot yeomen,” wrote Chaplain John W. Hanson, who chronicled the Sixth Massachusetts through three wartime campaigns.

What a sight they must have made as they mustered on the Common, each company in its own uniform. Privates Ladd and Whitney from Lowell wore grey dress coats, caps and pantaloons with buff epaulettes and trim, while Corporal Addison from Lawrence wore a dark blue frock and red pantaloons, “in the French style.” Company A volunteers sported blue frocks and black pantaloons with tall round hats and white pompoms.

Unifying their appearance somewhat were the grey woolen greatcoats issued to all. Standard blue uniforms would come later, including the signature forage caps. The men were also issued Springfield rifles and pistols for the officers.

At the State House on April 17, Governor John Andrews addressed the recruits:

“Soldiers,” he said, “summoned suddenly, with but a moment for preparation…. We shall follow you with our benedictions, our benefactions, and prayers.” He then presented the regimental colors to Colonel Edward F. Jones, the regimental commander from Pepperell.

The next morning, April 17, to the ringing of bells, band music, gun salutes and the cheering of thousands, the 700-plus men of the Sixth Massachusetts boarded a train bound for the nation’s capital.

At each stop, Worcester, Springfield and Hartford, crowds cheered them on their way. Reaching New York that night, the men were feted with dinner and speeches. The next day they crossed by ferry to Jersey City, then by train to Trenton. Arriving that evening in Philadelphia, the troops received their most enthusiastic reception. Wrote Chaplain Hanson: “So dense were the crowds that the regiment could only move through the streets by the flank.”

That night in Philadelphia the officers “were entertained sumptuously” at the Continental Hotel, while the soldiers were quartered at the Girard House. Weary from travel and excitement, they were grateful for the chance to sleep. Their rest, however, was cut short when roll was called and they were ordered back to the train station. At 2 a.m, the Sixth Massachusetts left for Baltimore. It was Saturday, April 19, 1861, four score and six years to the day after Minutemen marched to Lexington and Concord to fight British Red Coats.

While the soldiers were sleeping, Colonel Jones had met with Brig. General P. S. Davis, sent ahead to arrange transport. Davis told him that pro-slavery agitators in Baltimore planned action against the Massachusetts infantry. Jones also met with the president of the Philadelphia and Baltimore Railroad, who sent a pilot engine ahead to scout for obstructions on the tracks. Insisting that they must push on to Washington, Davis hoped to arrive in Baltimore before a crowd could assemble.

In the spring of 1861, Maryland was still a slave state, although it had not joined the Confederacy. While the mayor of Baltimore had promised safe passage of the Sixth Massachusetts, many Maryland citizens viewed their passage as an intrusion, if not an invasion.

Because steam engines could not pass through Baltimore, trains from Philadelphia had to stop at the north depot and the cars uncoupled. They would then be pulled by horse teams along tracks to Camden Station, the south depot, where they would be hooked to another engine headed south.

Arriving in Baltimore about 10 a.m., the Sixth Massachusetts at first faced little trouble. Wrote Hanson: “As soon as the cars reached the station, the engine was unshackled, horses were hitched to the cars, and they were drawn rapidly away.” So far, they had caught protesters unaware.

By the time the seventh rail car began its course, however, a mob had gathered and begun hurling insults, bricks and stones. It got worse the further they went, and three times was car was knocked off the tracks, then set back.

Fearing violence, officers had earlier issued 20 cartridge balls to each soldier and ordered their rifles loaded and capped. But they were not to fire unless fired upon.

After the seventh company reached Camden Station, Mayor George Brown signaled that “it is not possible for more soldiers to pass through Baltimore unless they fight their way at every step.” Yet there were still four more companies, two from Lowell, one from Lawrence and one from Stoneham, waiting to cross. Included was the regimental band.

Thousands now blocked the streets, tore up paving stones, and dragged debris onto the tracks. Unable to move the last two cars, the four companies disembarked and began to march. Lt. Leander Lynde from Stoneham would later write:

“What impressed me most at the time was the terrible fury of the mob…. Not content with hurling flagstones, bricks, hot water, flatirons and every conceivable thing, the mob hissed us, called us names and taunted us with monstrous vocabulary. Even the women hurled things at us from windows.”

Lynde himself was struck in the head by a brick. “I fell stunned for a moment. The boys picked me up, thinking that I was dead, but I soon recovered and marched on with them.”

Leading the four companies was Captain A. S. Follensbee of Lowell: “Before we had started, the mob was upon us, with a secession flag, attached to a pole, and told us we could never march through that city. They would kill every ‘white nigger’ of us, before we could reach the other depot.”

As he stepped down from the train, Corporal Sumner Needham of Lawrence told a fellow soldier: “We shall have trouble to-day, and I shall never get out of it alive. Promise me, if I fall, that my body shall be sent home.”

Falling in, the companies pressed forward through a sea of rioters. Showered with missiles, the men doubled their pace. “We had not gone more than 10 rods further before I saw a man discharge a revolver at us from the second story of a building, and at the same time a great many were fired from the street,” wrote Lynde.

One of the first to fall was Lynde’s company captain, John H. Dyke, shot in the thigh. Wrote Lynde, “I decided it was about time for me to take the responsibility and ordered my men to fire upon the mob. The men in the other companies at once joined in with us.”

Especially vulnerable was the color guard—Color Sergeant Timothy A. Crowley of Lowell—who carried the flag, and his aides, Ira Stickney and W. Marland. Another company chaplain, Charles Babbidge, remembered: “Paving stones flew thick and fast, some just grazing their heads and some hitting the standard itself. One stone, as large as a hat, struck Marland just between the shoulders, a terrible blow, and then rested on his knapsack. And yet he did not budge. With a firm step, he went on, carrying the rock on his knapsack for several yards, until one of the sergeants stepped up and knocked it off.”

When they reached the Pratt Street Bridge, they found a crowd had pulled up the planking, so “we were forced to creep over as best we could on the stringers,” wrote Lynde.

Arriving finally at Camden Station, the last four companies found the doors of the waiting cars locked, but used their rifle butts to gain access. Now in charge of Company L, Lieutenant Lynde saw his company and the color guard safely aboard. They were surrounded, however, by another huge crowd brandishing guns, knives and clubs. Running ahead, the mob placed telegraph poles, anchors and stones on the tracks.

Slowly, with rifle muzzles sticking out the windows, the train began to move. The engine stopped and men jumped out to clear the obstacles. The train started again and stopped. A rail had been removed. It was replaced, and again the train was in motion.

“The crowd went on for some miles out,” Chaplain Hanson wrote, “as far as Jackson Bridge, and the police followed removing obstructions; and at several places shots were exchanged.” At the Relay House, the train was held up until a train coming north had passed. Then it continued, unobstructed, to Washington.

On the train, the officers counted their casualties and the missing. Dozens had been wounded, and dozens more missing, including the regimental band.

Unarmed, the musicians had refused to march through the city. However, this did not stop the attackers. One musician, A. S. Young of Lowell, recalled: “We fought them off as long as we could; but coming thicker and faster . . . they forced their way in.” Fleeing the cars, one band member was urged by a policeman to “run like the Devil.”

Seventeen-year-old Victor Lorendo of Stoneham escaped by diving under the rail car, then racing off. Tearing the stripes off his pants so he wouldn’t be recognized, he somehow made it back to Philadelphia and eventually Boston. He then walked the last ten miles to his home town. He had been reported dead.

Not all citizens of Maryland were hostile. In several cases, shop owners and housewives sheltered and cared for wounded soldiers. Fleeing the mob, a number of the band members were rescued by “a party of women, partly Irish, partly German, and some American, who took us into their houses, removed the stripes from our pants and we were furnished with old clothes of every description for disguise,” wrote Young. Sheltered and fed, the musicians returned two days later to Philadelphia.

Meanwhile, the soldiers on the train wondered what kind of reception they would have in Washington. It was dark when, just four days after the President’s call, the locomotive steamed into the capital. To their relief, they found a crowd cheering their arrival. Among them was a Massachusetts woman who worked in the Patent Office. Her name was Clara Barton and she had come to the capital to organize nursing and relief services. As the injured left the train, she and her assistants dressed their wounds and arranged transport to area homes.

The rest of the regiment marched to the Capitol, where they bedded down in the Senate Chamber. It was a strange scene. “The colonel was accustomed to sleep in the Vice President’s chair, with sword and equipments on,” wrote Hanson. “The rest of the officers and men were prostrate all over the floor around him, each with sword or musket within reach ; the gas-lights turned down to sparks, and no sound but the heavy breathing of sleepers and the hollow tramp of sentinels on the lobby floors.”

On Sunday morning, April 20, the Sixth Massachusetts marched “in open order” up Pennsylvania Avenue, giving the appearance of a full brigade, so as to “intimidate the secessionists.” At the White House they were welcomed by a grateful President Lincoln and Secretary of State William Seward.

Over the next few days the Sixth Massachusetts cheered the arrival of the Seventh and Eighth Massachusetts as well as regiments from New York, Pennsylvania and Rhode Island. Setting up defenses around Washington, they prepared for a Confederate attack.

Back at the Capitol, the soldiers had time to write letters, and the officers to submit reports. Describing the ambush in Baltimore and casualties to his company, Lieutenant Lynde wrote:

“Captain Dyke was shot in the thigh…. James Keenan was shot in the leg, and Andrew Robbins was shot and hit with a stone, hurt very bad. Horace Danforth was hit with a stone and injured very severely, but all were in good hands and well cared for.”

What happened to Capt. John Dyke after he was shot was told later by Chaplain Hanson. Hobbling into a tavern, he was met by a Union sympathizer, who carried him to a back room. “He had scarcely left the barroom . . . when it was filled with the ruffians, who, had they known his whereabouts, would have murdered him.” Nursed and cared for, Dyke remained there for a week before being sent, disabled, back home.

Of the 67 in the Stoneham company, 18 had been wounded by gunshot, bricks or paving stones. The volunteers “had been worked very hard for green soldiers,” Lynde wrote, “but the men have done well and have stood by each other like brothers.”

Also attacked were the companies from Lowell and Lawrence, which, like Stoneham, had been forced to cross Baltimore on foot. Lowell’s Company D, marching on the exposed left side of the column, was especially hard hit. Nine men were injured, including Sgt. William H. Lamson, wounded in the head and eye from paving stones, and Sergeant John E Eames. From Lawrence, Alonzo Joy had his fingers shot off, and George Durrell was injured in the head by a brick. Three others were wounded.

From the two mill cities, four were killed. The first was the 17-year-old mechanic from Lowell. Having grown up on a farm, Luther Ladd had followed three older sisters to work in the textile industry. “He was full of patriotic ardor,” Hanson wrote. “When the call was made for the first volunteers, the earnest solicitations of his friends could not induce him to remain behind.” Marching along Pratt Street, Ladd was struck in the head and shot, the bullet severing an artery in his thigh. He is considered the first Union soldier killed in the Civil War.

Also in Company D, Addison Otis Whitney, the Lowell spinner, was shot and killed. Born in Waldo, Maine, he was 22. Before enlisting in the Sixth Massachusetts, he had joined the City Guards.

The third soldier in Company D to perish was Charles A. Taylor, of whom little is known. Taylor enlisted at the last minute, wrote Chaplain Hanson, “and represented himself as a fancy painter by profession, about 25 years old, and was of light complexion and blue eyes.” A bystander later reported that Taylor, having fallen, was beaten to death by ruffians and his body thrown in a sewer. As Taylor wore no uniform but the regimental coat, his death was not confirmed until a bystander later returned the coat to a Union officer.

After the war, Col. Edward Jones made several trips to Baltimore to find Taylor’s body and return it to Massachusetts, but the burial site was never found.

The fourth fatality was Corporal Sumner Needham of Lawrence’s Company F, who had voiced a presentiment of his death in Baltimore. Struck by a paving stone, Needham fell to the ground, his skull fractured. A surgeon tried to drill a hole in his skull to relieve the pressure, but in vain. The 33-year-old corporal died a few days later. In December, eight months later to the day, his wife, Hannah, gave birth to a son.

On May 2, Needham’s body, along with Ladd and Whitney, were returned to Massachusetts, where they were viewed by thousands at King’s Chapel and eulogized at the State House. They were then conveyed by train to Lowell and Lawrence. Needham lay in state in Lawrence City Hall before burial in Lawrence’s Bellevue Cemetery. The inscription on the granite memorial reads, in part, “[Needham] fell victim to the passions of a Secessionist Mob, during the passage of the Regiment through the streets of Baltimore marching in Defense of the Nation’s Capital.”

Meanwhile in Lowell, throngs turned out to receive the bodies of Ladd and Whitney, who, like the others, were mourned as martyrs in the cause of freedom. For the funeral, residents crowded into City Hall to hear clergy from seven churches officiate.

On June 17, four years later, Governor John Andrew dedicated a 27-foot-high obelisk memorial, honoring “the first soldiers of the Union Army to die in the great rebellion.” On it are the names of Ladd and Whitney. Later a brass plate with the name of the Charles Taylor was added.

Although the Sixth Massachusetts volunteers were the first to arrive at the nation’s capital, they did not participate in the humiliation of Bull Run, which took place on July 12. By this time, they had been ordered back to Maryland, as the state was now put under martial law. Taking control of its forts, ports and rail lines, the Sixth would in three months complete its first campaign and return home. Most of the men would re-enlist, either in the Sixth or other Massachusetts regiments, engaging in conflicts through the end of the war.

In the April 19 ambush in Baltimore, sometimes called the Pratt Street Riot, the yeoman soldiers of the Sixth Massachusetts faced bullets, stones, and the hate of a pro-slavery mob. It was not Manassas, Antietam or Gettysburg, but it was the beginning. The volunteers from New England were attacked not by Confederate soldiers, but by fellow American citizens whose lust for insurrection would fuel a long and bloody war. The ambush was vicious and it took the lives of four Union soldiers and twelve civilians. It wounded, many severely, thirty-eight soldiers and dozens of rioters.

The battle in the streets was the “first blood” of the War of the Rebellion, a cataclysm that raged across our nation for four more years and took the lives of three quarters of a million. The scars are with us today.

Sources include:

Hanson, John W., Chaplain. A Historical Sketch of the old Sixth Regiment of Massachusetts Volunteers during its Three Campaigns. Lee and Shepherd, Boston, 1866.

Hurd, D. Hamilton, History of Middlesex County, Massachusetts. J.W. Lewis & Co, Philadelphia, 1890.

Stevens, William B., History of Stoneham, Mass., F. L. & W. E. Whittier, Stoneham, Mass., 1891.

“The Pratt Street Riot,” National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/fomc/learn/historyculture/the-pratt-street-riot.htm, updated Feb. 26, 2015.