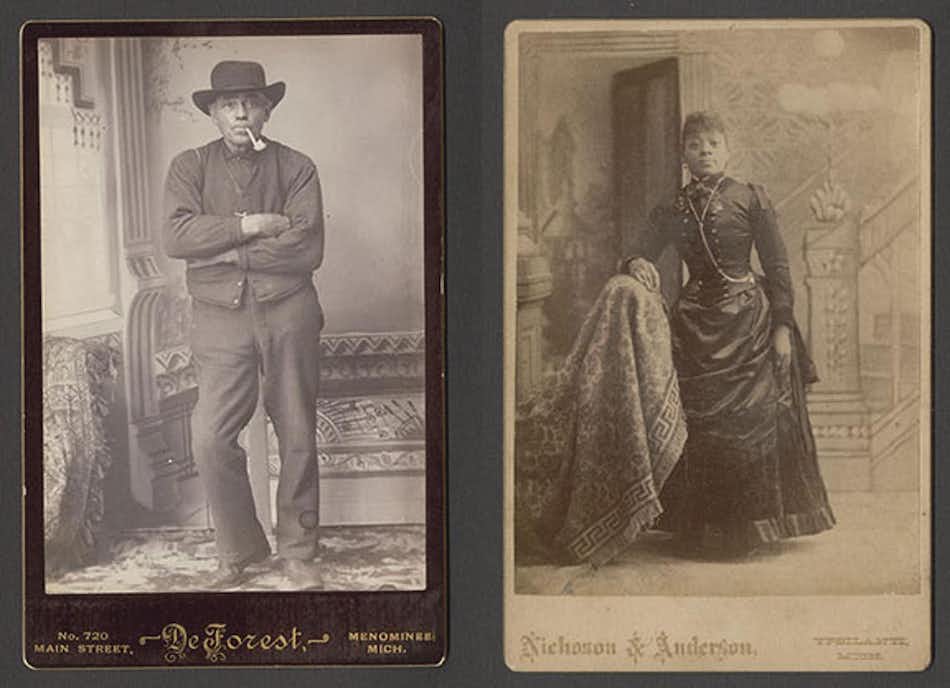

This is a story about Charles Cephas, a Black man who came to our town after the Civil War. On his gravestone in the soldiers’ lot at Lindenwood Cemetery, you’ll see he served in the U. S. Navy.

Charles was born in 1844 in Norfolk, Virginia. He may have been enslaved. One year after the Emancipation Proclamation, he joined the Union Navy and was inducted aboard the USS Ohio in Boston. He was then assigned to the USS Sacramento, which served to blockade Confederate ships off South Carolina and in Europe.

Discharged after the war, Cephas settled in Stoneham, Massachusetts. On August 13, 1867, as reported in the Stoneham Independent, he appeared before Silas Dean, justice of the peace, with his bride. Her name was Sarah Cecelia Hill, and she was from Brooklyn. He was 23, she was 18. In Stoneham they would raise five children, three sons and two daughters.

I don’t know what Charles Cephas looked like, but he must have been a man of considerable strength. I say that because he was a mason, a well digger, an earth mover. An ad in the Stoneham Independent reads: “The services of Charles Cephas stone mason can now be had. He tends to laying pipes, sinking wells, digging cesspools and blasting. ‘He thoroughly understands his business.’”

That same year the newspaper reported that “Charles Cephas is digging and stoning a well in Montvale, which he thinks will be the deepest in Woburn. It is 35 feet deep.”

In the 1870 federal census, Charles and Sarah are two of only 27 “non-whites” listed in a town of 3,444. Yet, from what I can find, they did all right, and by 1876 purchased their own home. In the Independent, we read: “Wm. Howell sold a house on Hancock Street to Charles Cephas, and the latter had had it successfully moved to Albion Ave in the north westerly part of the town. Ellis of Malden did the moving.”

But life for the Cephas family had its rough parts. And here the story gets complicated. It’s complicated, because if we are to know the tenor of Charles Cephas’s life, we must acknowledge the persistent prejudice African Americans faced, not only in the South, but in booming factory towns like Stoneham. His story raises questions that make us uneasy.

Most of what we know about Cephas comes from the Stoneham Independent. There are also census reports and vital records. We also have notices of court actions, arrests and fines. Sometimes, we have to read between the lines.

I don’t know if Charles was enslaved in Virginia. He may have been. Certainly, his desire for freedom, his enlistment in the Union Navy, and his insistence that he be respected as a free man played out in his daily life. He didn’t always get respect.

Disturbing the Peace

Although Charles Cephas found Stoneham a good place to start a business, a place where hard work was rewarded, he was also learning that even in the North men who looked like him could become targets of abuse.

In 1878, as reported in the Independent, five men, aged 16-25, attacked and beat Cephas and Thomas Shanks, another Black man. Arraigned in court for assault and battery, the men were fined and released.

There were other times, however, when Cephas was the one being charged. For example, in 1891 at the P Cogan & Sons shoe factory on Main Street, where he was arrested for disturbing the peace.

According to the Independent, Charles Cephas was walking beside the Cogan plant when, from an upstairs window, someone dumped a bucket of whitewash onto him. Furious, he rushed into the mill in search of the culprits. Not surprisingly, no one admitted the racist prank. Cephas was “pretty well worked up,” wrote the reporter, “and may have talked pretty loud, for Officer Newton appeared on the scene.”

Rather than find the perpetrator, however, the officer “arrested Charles and started for the ‘lock-up.’” When Cephas resisted, the policeman enlisted “one or two outsiders for aid” and hauled him off to jail.

Another time, according to the papers, Cephas threatened to blow up the Stoneham police force. The Boston Globe, which picked up the story, told it like this:

Early this morning an officer saw a young man chasing a girl along a street. The latter was shouting for assistance. The officer hailed the man, who stopped and was informed that he was under arrest. The man, who proved to be Charles Cephas, refused to be taken into custody and opened a handbag he carried, and told the officer the contents were dynamite, and if he was molested he would explode the same.

The Independent gave more detail, alleging that Cephas, uttering profanity, had chased a “Miss Kelly” to the home of Officer Green, where she sought protection. Green and another officer confronted Cephas, who was standing in the street, and told him to go home or be arrested. Cephas started, but then stopped, warning the officers that he had dynamite in his bags and would blow “the whole —- police force up” if they came near.

On Monday Cephas showed up in court and paid a fine of $10 for disturbing the peace. He told the judge that he couldn’t remember threatening “to blow up the police force,” but if he did, “he was sorry.” No mention was made of the altercation between Cephas and the young woman.

Looking back at Charles Cephas, we see a puzzle with many pieces missing. We will never get a full picture. Still, what we have suggests the complexity of his life in our town. We also learn a little about his family, about their losses and achievements.

In 1869 the Independent listed the death of a son, age 1. Infant deaths were also recorded in 1874 and 1883. In the notes section of an 1885 edition, we read: “Mr. Charles Cephas has had the misfortune to lose one of his youngest children lately.”

In October of 1884 Sarah (also known as Cecilia or Celia) posted a card thanking family friends in Woburn, Wakefield and Stoneham “for their many kindnesses and sympathy in her late bereavement.”

But there were also good times, such as the wedding of their son, George, to Carrie H. Yancey. It was “a very pretty home wedding” reported the Independent, “performed in the presence of a large company of friends.”

In another story we learn about an ice-hockey game on Spot Pond in which the Stoneham team beat Salem 1-0. The ice was rough, the paper reported, due to the many ice yachts that had been racing on the pond. Playing with the Stoneham team was Ernest Cephas, George’s brother.

There is evidence that the Cephas boys learned shoemaking trades. Ernest, however, seems to have something else in mind.

In 1887 we find out that Ernest has gone to sea. Like his father, he enlisted in the Navy. Home on leave in 1896, wearing his sailor’s uniform, he was returning from Woburn late one night when he was accosted by several toughs, who berated him with racial slurs.

Getting off the trolley at the last stop, Ernest stepped up to the gang leader “and lit into him like a cyclone,” giving him “such a pummeling as he probably never had in all his life.”

Although Ernest was later charged in court, the Independent clearly took his side. The headline ran: “He Deserved It!—Ernest Cephas Teaches a Haverhill Tough a Wholesome Lesson.”

Two years later, during the Spanish-American War, Ernest was serving aboard the Navy cruiser USS Brooklyn. In a letter published by the newspaper, he described in dramatic detail a victorious battle between American and Spanish warships.

Of the Cephas’ third son, Louis, born in 1876, we know very little. His name does appear, however, in a news report of the 1904 trolley car disaster in Melrose. Lewis was riding in the car when dynamite carried by workmen exploded. Nine passengers were killed and 30 wounded. Blown into the street, Louis survived with cuts and bruises from flying glass and debris.

Of the two surviving daughters, Eva, born in 1883, and Sarah, born in 1887, there is also little information. Records show that Sarah married John Addison in Boston in 1912, and that Eva married a man with the last name of Carter in 1913.

Coming Home

Charles and Sarah Cephas were not the only African Americans to settle in Stoneham after the Civil War. There were also the Yanceys, Freemans, Reeds and others. In the Independent, we find mention of “a Mr. Curtis and a Mr. Turner, [who] owned adjoining lots on Albion St. in 1874.” Also noted was the Lewis family, “that married into the Yancey family.”

For the Black families, Stoneham was a good place to put down roots. But the soil could also be rocky, in more ways than one. For Charles Cephas, getting along in an overwhelmingly white community inevitably involved conflict.

On at least one occasion, reported in the press, he was assaulted. Other times, he was charged with disturbing the peace, including the time workers at a shoe mill dumped whitewash on him.

His marriage was another story. We can never know the complexities of any marital relationship. But the stresses of his life must have crossed over to his marriage. In the Independent on March 9, 1895, we learn that Sarah Celia Cephas, after 28 years, has petitioned the Middlesex Court for divorce and that “a decree of divorce was given.”

Sometime after this, Cephas moved out of Stoneham. In 1899 we find him living in Chelsea and working at the Charlestown Navy Yard, where he continued for another nine years. Until June 10, 1908.

What happened on that date is unclear. It was not reported on, as far as I can tell, by any Boston papers. Nor, does it seem, were the police involved. It was, however, reported on by the Independent. Here is what the Stoneham newspaper said on Saturday, June 20:

Charles Cephas, colored, passed away Wednesday evening of last week, at the Chelsea Marine hospital, as the result of injuries received by being assaulted as he was coming out of the Charlestown Navy Yard, where he has been employed as a stone mason. He was about 65 years of age.

The paper then speculated that “the object of the assault was robbery, his assailants evidently being after Mr. Cephas’ pension money.”

After listing the five names of his surviving children, the Independent continued:

The deceased was a Civil War veteran, having served four years in the Navy. Until about 15 years ago he was a resident of this town for thirty years. He was born in Virginia in ante-bellum days.

Funeral Services for Cephas were held in Chelsea. But for burial he was brought back to Stoneham, interned in the Civil War memorial lot at Lindenwood cemetery. Was there an honor guard present, as there often is for veterans? No mention is made.

Looking back at the demise of Charles Cephas, we are left with questions. Why did his brutal murder in Charlestown receive so little attention? Was there no police report? Was there no attempt to apprehend and prosecute his killers?

I was able to find the Chelsea coroner’s report, filed a week after his death. The cause of death was listed as “acute fibrinous pneumonia consequent on hemorrhage and laceration of the brain sustained under circumstances unknown, probably those of an accidental fall.” Accidental fall? Really?

Back in 1891, when Cephas was still living in Stoneham, the Independent reported that “People on the outskirts of town complain of dry wells. Will it ever rain in earnest?”

In that same issue was the news of Charles Cephas digging a 35-feet-deep well, “the deepest in Woburn.”

When I think of Charles Cephas, I like to think of this.

Charles Cephas came to Stoneham looking for a place he and his family could call home, and in doing so, he helped build our town. Although his story is complicated by factors we can only partially understand, it challenges us to look honestly at history and ourselves.

His story is part of our history. It is our story as well.

Notes: The Cephas, Reed and Yancey families are featured in an exhibit at the Stoneham Historical Society & Museum, titled “150 Years of Service.” You can see the online version at https://stonehamhistoricalsociety.org/exhibits/150-years-of-service-the-cephas-reed-and-yancey-families-online-exhibit/

Thanks to Joan Quigley, historian and archivist at the Stoneham Historical Society & Museum, and Dee Morris, Medford historian, for their help in researching the Cephas family.

Ben Jacques is the author of In Graves Unmarked: Slavery & Abolition in Stoneham, Massachusetts, and If the Shoe Fits: Stories of Stoneham Then & Now. Both are available at the Book Oasis on Main Street. He also writes essays, poems and articles, many of them found on his blog at benjacquesstories.com.