They Were Brave and Bold – Beowulf .

Denmark needed a superhero. A treacherous monster named Grendel was savaging them at night, slaughtering their best as they bedded in Heorot, the great hall of the king. Thus the stage was set for Beowulf, a brawny prince who crossed the sea from Geatland to rid the Danes of evil.

The prototype of the Western superhero, Beowulf does what neither King Hrothgar nor his warriors can do. He vanquishes both Grendel and the slayer’s vindictive mother, diving into a black sea, writhing with snakes, to bring an end to oppression.

Yet in the end, fifty years later, neither Beowulf’s strength nor courage can protect the people from the evil destroying their cities. It takes the wisdom of a thane, an underling named Wiglaf, to see that it is not enough to have heroes if the people’s hearts have grown cold.

We know the story as the first great epic in our language, not English as we know it, but Anglo-Saxon. Sung then written down around 900 CE, it was crafted by a descendant of the Angle, Saxon, Jute and Frisian invaders who overwhelmed Celtic Britain in the 5th and 6th centuries. The translation I like best is by the late Irish poet, Seamus Heaney.

A pagan saga with a Judeo-Christian overlay, Beowulf portrays a world in flux. Most modern tellings focus on our hero’s two great victories in Denmark. By the time we get to Beowulf’s last battle, however, things have changed. In several passages, blending Biblical narrative with a pagan’s rumination on the transitory nature of life, the poet reveals a shift in values.

In Beowulf’s world—as today—men seek gold, weapons and treasure. These give them status. With them, kings and queens gain allegiance, reward subjects and build alliances. Treasure shared holds the community together. Treasure hoarded leads to treachery. Hrothgar showers Beowulf with fine gifts: horses, fine armor “and a sword carried high, that was both precious object and token of honour.”

At the same time the king counsels the young warrior to remember he too is mortal. He warns him against vanity and pride, “an element of overweening” that will lull his soul to sleep and expose him to the enemy.

Pride and the lure of treasure surface again in the final act of the play, as Beowulf, now an old king, goes out to battle a “slick-skinned dragon, threatening the night sky with streamers of fire.” Guardian of an ancient underground barrow, the dragon has been burning farms and villages across Geatland, all in revenge for a jeweled cup stolen from its hoard.

Wanting to protect his people, Beowulf is “too proud to line up with a large army against the sky-plague.” He will face the monster alone, confident he will prevail as he did against Grendel and his mother.

It is not to be. In desperate combat, Beowulf is mortally wounded. His famous sword, Naegling, breaks against the dragon’s scales, and the monster’s teeth penetrate his armor. Beowulf slays the dragon, but only with the help of Wiglaf, a young Geat warrior who could not bear to see his king go into battle alone.

As he is dying. Beowulf asks Wiglaf to gather samples of the dragon’s treasure, so he can feast his eyes on them:

I want to examine

that ancient gold, gaze my fill

on those garnered jewels (2747-9)

But the value of gold, jewels, fine weapons and armor—even the priceless cache found in the dragon’s hoard—is relative. Nowhere is this better expressed than in what happens next. Instead of using the treasure to enrich the kingdom, the Geats heap it onto Beowulf’s funeral pyre. They bury the rest in a great mound on the headland by the sea.

They let the ground keep that ancestral treasure

gold under gravel, gone to earth

as useless to men now as it ever was (3166-8).

Nearing the end of the epic, we sense a turning from sword power to soul power. Valued most highly now is inner strength, not physical prowess. The enemy are no longer dragons and monsters, but human rivals—Swedes to the north and Franks and Frisians to the south.

At Beowulf’s funeral, there is great sorrow, but also great fear:

A Geat woman too sang out in grief;

with hair bound up she unburdened herself

of her worst fears, a wild litany

of nightmare and lament, a nation invaded,

enemies on the rampage, bodies piled up,

slavery and abasement (3150-5).

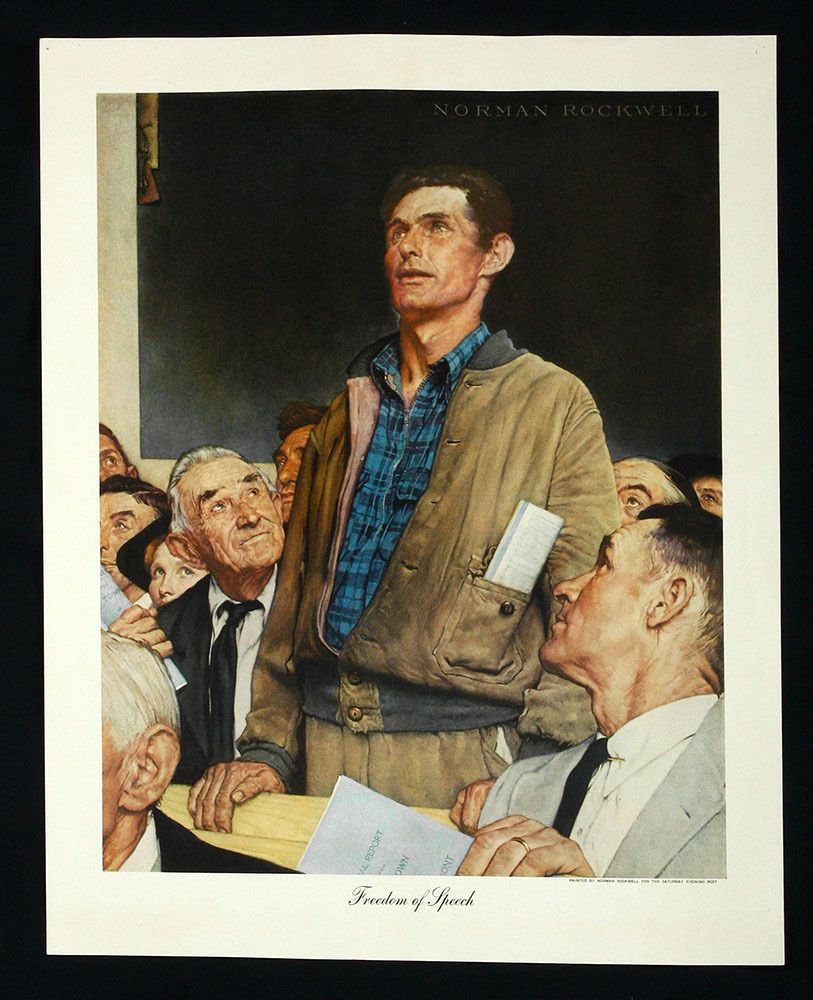

Wiglaf sees clearly what is to come. In a scathing rebuke, he tells his people they have lost more than a great king. They have lost their heart. It is true—their king chose to go into battle alone. Yet, when his warriors saw him bested by the dragon, they turned and ran.

The tail-turners, ten of them together,

when he needed them most, they had made off (2848-9).

Now, weakened by cowardice, Geatland is ripe for the picking.

So it is goodbye now to all you know and love

on your home ground, the open-handedness

the giving of war-swords. Every one of you

with freeholds of land, our whole nation

will be dispossessed (2884-8).

Wiglaf knows that no amount of treasure, or armaments, will protect a people who are paltry of spirit, who abandon each other in times of peril. More important than gold or brawn is the steel of a person’s heart, which underlies all strength. In a remarkable description of interior growth, Wiglaf reveals the change that occurred in him when he ran to assist his beloved king:

There was little I could do to protect his life

in the heat of the fray, yet I found new strength

Welling up when I went to help him.

Then my sword connected and the deadly assaults

of our foe grew weaker (2877-80).

Wiglaf’s experience has given him insight into the interior world through which a warrior must journey. His wisdom makes our first English epic as relevant to our time as to his.