June 19, 2025

Dear Mr. Cephas,

You came north after the Civil War, a Black man from Norfolk, Virginia, looking for a place to work and raise a family. You chose us, Stoneham, Massachusetts, a shoe-factory town of about 3,500 people just north of Boston.

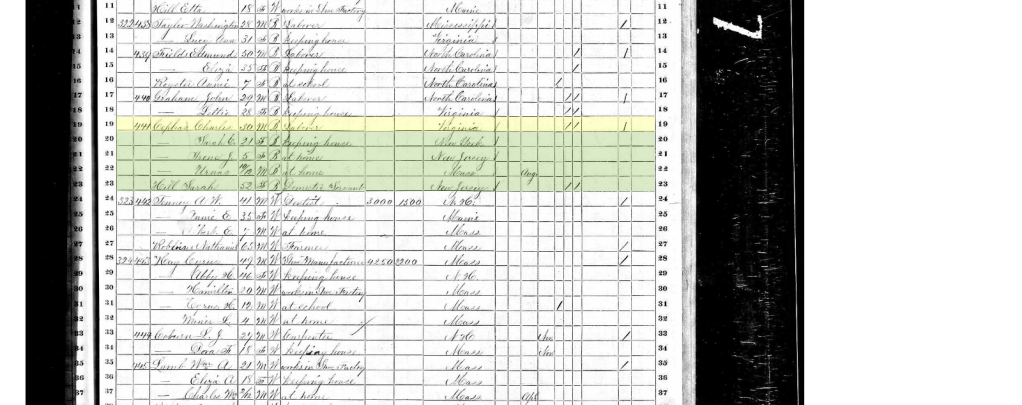

In Virginia, were you enslaved? I could find no record. I did find that the year after the Emancipation Proclamation you enlisted in the Union Navy and spent a year aboard the USS Ohio. The Ohio was used to blockade Confederate ships along the Carolinas and in Europe.

In 1867, two years after the war, you appeared before the Justice of the Peace in Stoneham with your bride, Sarah Cecelia Hill, from Brooklyn. You were 23 and she was 18. With her you would raise five children, three sons and two daughters.

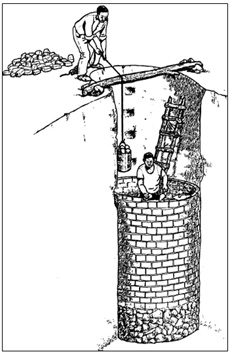

I don’t know if you were tall or short. I do know you were strong. I found this ad in an old Stoneham Independent: “The services of Charles Cephas stone mason can now be had. He tends to laying pipes, sinking wells, digging cesspools and blasting. ‘He thoroughly understands his business.’”

Remember that summer when people were praying for rain, you made the news when you dug and lined a 35-foot-deep well, a record in Woburn.

Business must have been good, because in 1876 you bought a house on Hancock Street, then moved it over to Albion Avenue on the northwest side of town.

For you and the few other African American families, Stoneham was a good place to put down roots. But the soil was rocky, in more ways than one. Getting along in an overwhelmingly white community sometimes meant conflict. Sometimes you were the target. In 1878, as reported in the Independent, five men attacked and beat you and your friend Thomas Shanks.

Another time, when you were walking by the Cogan and Sons shoe factory, from the upstairs window, someone dumped a bucket of white wash on your head. Furious, you stormed into the building demanding to know who the culprit was.

You raised such a fuss that the police were called. But instead of helping to find the offender, the police arrested you and charged you with disturbing the peace.

Another time, faced with arrest after a domestic dispute, you threatened to blow up the police station with dynamite you had in your work bag. Appearing in court the next day you stated you couldn’t remember making such a threat, but if you did, you were sorry. You were fined $10.

Were there good times? Did you and Sarah get together with other families after church for dinner? Your children would have gone to school in town.

In 1902 the Independent reported the wedding of your son, George, to Carrie Yancey. It was “a very pretty home wedding, performed in the presence of a large company of friends.”

Another time we learn of your son, Ernest, playing hockey on Spot Pond. Earnest would later go to sea, serving in the U.S. Navy during the Spanish American War.

There were painful losses, as the loss of your firstborn son, Charles H. Cephas, age one. Infant deaths were also recorded in 1874 and 1883.

At some point the stresses of life must have crossed over to your marriage. In 1895, after 28 years, your wife petitioned the Middlesex Court for divorce, and it was granted.

Sometime after this, you moved to Chelsea and started working as a stone mason at the Charleston Navy Yard. I couldn’t find any more about you until 1908, when I found this in the Stoneham Independent:

Charles Cephas, colored, passed away Wednesday evening of last week, at the Chelsea Marine hospital, as the result of injuries received by being assaulted as he was coming out of the Charlestown Navy Yard.

The reporter speculated that your killers must have been after your pension money.

Although there was no mention in the Boston papers, I did find a copy of the coroner’s report. It stated the cause of death as “acute fibrinous pneumonia consequent on hemorrhage and laceration of the brain sustained under circumstances unknown, probably those of an accidental fall.” Accidental fall? Really?

After a funeral in Chelsea, they brought you back to Stoneham for burial in the Civil War military section. Was there an honor guard? On Memorial Day I stopped by Lindenwood to pay my respects.

Sometimes I wonder what you would make of our town today. Of our nation. Some things are better. Some not.

There’s so much that would amaze you. So many stories of African Americans who paved the way in education, music, science, law enforcement, athletics, and business, not only on the national stage, but in our own town, some of them your descendants.

If I tell you about the achievements, however, I also have to mention the set-backs. I have to tell you about George Floyd.

But here’s something to celebrate. Did you know we now celebrate Juneteenth, the date in 1865 when enslaved folk in Texas finally found out they were free?

Mr. Cephas, when I think of you, I think of a man digging wells so families can have water. I think of a stone mason, his hands rough with callouses. I think of a man who had a temper, but who wanted, above all, a safe place to live, work and raise a family. Who deserved more respect than he got.

Happy Juneteenth, Mr. Cephas.

Ben Jacques

Stoneham