When Marco Rubio announced recently that the State Department was switching its official typeface, I wondered what was going on. Having taught a course in typography, I am well aware of type design and the nuanced notions associated with certain fonts.

I also immediately thought of a typeface called fraktur, a Germanic font Adolf Hitler loved, then hated, and the controversy over typefaces during the Third Reich.

The typeface Rubio doesn’t like is Calibri. It’s a standard sans-serif font. For many years it was the default in Microsoft programs, most recently replaced by a similar one called Aptos.

“Sans serif” means the letters are simple strokes without serifs, the little hands and feet at the end of lines. There is also no variation in the width of the lines. Their development was part of the avant garde movement in art, meant to express simplicity and modernity.

One of many sans-serif fonts in the modernist or humanist style, Calibri was created by Dutch typographer Lucas de Groot. With clean lines and slightly rounded corners, it is easily readable in print and online and often selected for presentations. Used during the Biden presidency, it is easier to read in small letter sizes and is considered more accessible for those with disabilities.

So, what’s wrong with it? According to Rubio, Calibri is too informal, not befitting the dignity and tradition of America. In a directive to all diplomats, Rubio mandated the use, instead, of Times New Roman, a traditional serif typeface. He called the use of Calibri by the previous administration a capitulation to DEIA–that’s diversity, equity, inclusion and accessibility. In short, Calibri is too “woke.”

But why Times New Roman?

One of many classic serif typefaces, Times New Roman was designed in 1931 as the typeface for the Times of London and has long been a go-to font for books and newspapers. Its condensed letter forms and spacing make it efficient for presenting large amounts of text. I use it occasionally, when I want a traditional look in my designs.

The hullabaloo about typefaces reminds me of what happened in Germany in the 1930s, just as the modernist typefaces were gaining popularity. It should not surprise you to learn that Adolf Hitler and the Nazis abhorred the sans serif designs. Instead, they wanted a typeface that would reflect their heritage and status as a Nordic power. They chose an old typeface called fraktur.

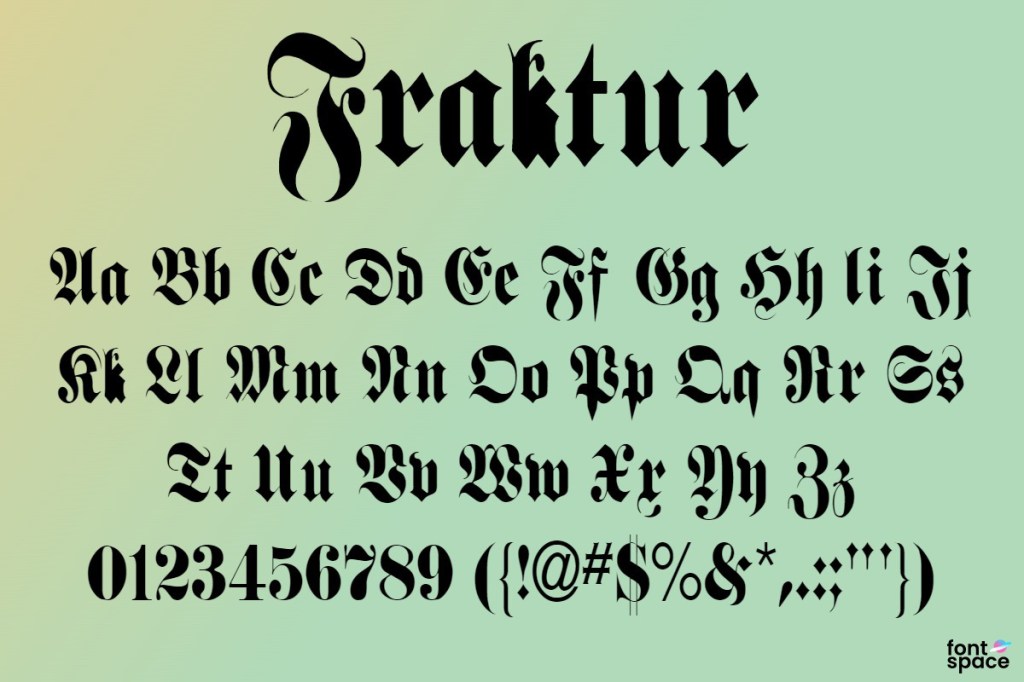

Fraktur is distinctly unlike both the modern sans serifs and the traditional “romans” in use throughout the Western world. Designed in the 16th century, it’s an updated version of a German blackletter, with thick, angular forms similar to what we know as Old English. As the official Nazi typeface in the 1930s, it was used in all government documents and propaganda.

That ended abruptly in 1941, however, when the Nazis discovered that the designer of fraktur was a Jew. In an about-face, the Nazis then outlawed its use and instead mandated that Antiqua, an old roman typeface, be used.

They say history may not repeat itself, but it rhymes. In this case, it chimes. In the current Administration’s need to change the design of the letter forms we use to communicate, it has revealed more about itself than it may have intended.

Yes, the typefaces we use can say a lot about us, even suggest the type of person we are.